Many Muslims today find it easy to claim that things are fobidden in Islam, without understanding. One widespread example is the prohibition on a hairstyle called qazaʿ :

Abdullah Ibn Umar (may God be pleased with him) said, ‘I heard God’s Messenger ﷺ telling people not to do the qazaʿ.’ (Sahih Bukhari)

I did not use the word ‘prohibit‘ in my translation above because not every nahi (instruction not to do something) automatically indicates impermissibility as it could indicate that something is disliked or discouraged. But whether it is prohibited or discouraged, what exactly is the qazaʿ hairstyle?

A widespread belief among Muslims today, including many preachers, is that it refers to any haircut where one part of the hair is shaved shorter than the rest (such as with fading), and this includes a great deal of haircuts popular among men today. But that is not what this word means.

Linguistically, the trilateral root (q.z.ʿ ) indicates something being light and scattered instead of being together. The word qazaʿ itself was used by the Arabs to refer to scattered patches of clouds in the sky. Thus, the great lexicographer Ibn Faris explains in Maqayīs al-Lugha that the qazaʿ is when a head is shaved and only scattered patches of hair are kept on the head.

Just like with scattered clouds, for a hair to be considered qazaʿ it would require small patches of long hair separated by completely shaved parts. This is how it was explained by the very narrator of this hadith in Sahih Bukhari: Nafi the servant of Ibn Umar. Imam Bukhari chose his narration in his Sahih because it comes with the explanation:

Nafi said: “It is when a boy has his head shaved leaving a tuft of hair here and a tuft of hair there. As for having longer hair on the temples or the back of the hair, there is nothing wrong with that. The qazaʿ is when a tuft of hair is left on a boy’s forehead while no hair is left on the rest of the head, and similarly when tufts of hair are left on either side but nothing in the middle . (Sahih Bukhari #5920)

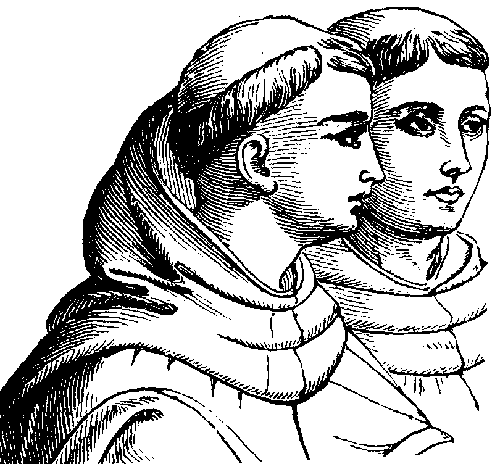

The earliest hadith commentators understood this to mean the Tonsure, a ritualistic partial shaving of the head found in many ancient religions to indicate belonging to a special religious class or spiritual order. The style described by Nafi above in Sahih Bukhari, of only the front of the head having hair while the rest being completely shaven, was originally a practice of the Druids (the priestly class in ancient pre-Christian Celtic cultures), and became the style of Christian Celtic monks after them, and is therefore known as the Celtic Tonsure. Below is an image of a famous druid sculpture showing the Celtic Tonsure:

The earliest work of substantial hadith commentary is that of the Central Asian mystic al-Hakim al-Tirmidhi (d. around 295 A.H.). He explained in his book Nawadir al-Usul that the qazaʿ refers to what is known as the Roman Tonsure, first adopted by Roman monks around the 5th Christian century as a symbol of abandonment of the world, and which later became a compulsory act of initiation into the Catholic clergy, until the Pope abolished this practice in 1972. It looks like this:

According to a report of uncertain authenticity, Abu Bakr al-Siddiq (may God be pleased with him) likened this hairstyle to a bird’s nest, remarking that Shaytan made a nest for himself on their heads (narrated in a disconnected chain in the Muwatta, and with a connected chain of uncertain authenticity in the Musannaf of Ibn Abi Shaybah).

Al-Hakim al-Tirmidhi commented on these words attributed to Abu Bakr, saying,

Abu Bakr meant that it was Satan who gave them this idea of making a visible marker for themselves and to make their lifestyle (of asceticism and abandonment of the world) visible for all to see. They are like those in our age who act like ascetics without sincerity, only seeking self-advertisement in their (outward) abandoment of the world, wearing (rough) wool or tattered clothes, shaving their moustaches (instead of just trimming them), exaggerating how much they roll up their sleaves and their lower garments, wearing turbans that wrap under their chins, and exaggerating the use of kohl all the way to the corners of their eyes. These are the signs of the deceptive class of fake ascetics (among the Muslims), seeking to devour the goods of this world (while pretending to leave them behind), by what they show others of their special clothes and appearance, their humble and pious demeanor being nothing but hypocrisy.

Al-Hakim al-Tirmidhi, Nawadir al-Usul, 5th asl.

In other words, the special attire chosen by many followers of the Sufi movement which began emerging in his era, is just as problemtic as the qazaʿ hairstyle.

After al-Hakim al-Tirmidhi came Abu Sulayman al-Khattabi (d. 388 A.H.), whose commentary on Sunan Abu Dawud, Maʿalim al-Sunan, was the first ever commentary on one of the canonical collections of hadith, and which remained for centuries the most influential and most famous work of hadith commentary in Islam. He explained the qazaʿ to refer to a boy’s head being completely shaven leaving only a ponytail, which is the Hindu version of the Tonsure known as the Shikha. The Shikha was meant to symbolise a one-pointed focus on a spiritual goal and devotion to God, and used to be considered an essential mark of all Hindus, but later only used by Hindu temple priests:

The prohibition on the qazaʿ (whether it indicates strict impermissibility or discouragement) does not apply to the fading done by so many barbers today. As indicated by the original Arabic usage of the word itself, it refers to an extreme hairstyle that shaves off most of the hair and keeps some scattered patches, which is an unnatural sight. It was also, in its different styles, a mark of devotion to different pre-Islamic religious orders and sects and therefore it is understandable why God’s Messenger (ﷺ) would instruct Muslims to avoid it. Finally, as the mystic al-Hakim al-Tirmidhi argued, it may also be discouraged/prohibited because it is a self-advertising marker of asceticsm, monasticism, or of belonging to a special class of a spiritual elite, of people claiming to have no attachments to the world and of being singularly devoted to God, while distinguishing themselves from others (and thereby seeking to draw attention to themselves and their unique status, and therefore trying to gain respect and honour from the world they supposedly reject – much like the woollen or patched garments and other such distinguishing features adopted by many Sufis of his era and later).